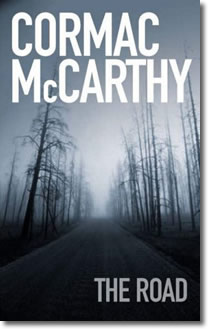

Revisiting The Road by Cormac McCarthy

Are we going to die now?

Are we going to die now?

No

What are we going to do?

We’re going to drink some water.

Then we’re going to keep going down the road.

Okay.

This stark exchange between a father and son captures the haunting nature of Cormac McCarthy’s remarkable novel, The Road, soon to be made into a full-length motion picture.

The novel is thoroughly apocalyptic. Survivors of global nuclear destruction or an environmental disaster (the novel does not specify), father and son travel on an unnamed road in the southeastern United States through a wasteland where nights are “dark beyond darkness and the days more gray each one than what had gone before.” They are always heading south, wanting to believe that at the ocean there may be life and warmth. These post-nuclear pilgrims scrounge for untainted food and water among deserted and ransacked houses, sleep in rusted cars, and take shelter from the permanent winter by camping under bridges. Hunted by cannibal bands, father and son are on constant guard for the evil marauders who patrol the road “casting their hooded heads from side to side . . . slouching along with clubs in their hands, lengths of pipe. Coughing.”

Be forewarned; this is one of the bleakest novels you will ever read—and one of the most hopeful. Therein lies its astounding appeal.

Horrors beyond imagining await father and son as they move from burned out cities through annihilated towns and ash-covered mountainsides. Artifacts of civilization—empty gas pumps, house trailers, shopping carts—are ghostly reminders of the world that is no more. Human remains litter the charred landscape. Leathered corpses stare out, grimacing from doorways. The father tries to protect his son from such terrors, saying “Just remember that the things you put into your head are there forever.” But the son has already seen.

The only thing that keeps them walking down this “barren, silent, godless” road is the father’s belief in the son, his reason for being. In one of the most telling lines of the story, the father is thinking to himself, “He knew that the child was his warrant. If he is not the word of God God never spoke.” Like mendicant friars, they venture out each day to find their keep. The father’s role, to protect the son. The son’s role, as his father has taught him over their years of fear and wandering, “to carry the fire.” Good guys, the father frequently reminds the son, “carry the fire.”

It is this sound of hope between father and son that gives deep scriptural resonance to The Road.For like ancient apocalyptic texts from Ezekiel to Revelation, the dry boned, doomed, and monster devoured civilization of the present can yet be redeemed by things to come. By God’s Spirit, the dry bones of Ezekiel’s vision in the Old Testament take on new flesh and live (see Ezekiel 37). The great conflagration of Revelation in the New Testament is quenched by the living waters of New Jerusalem (see Revelation 21-22) And in McCarthy’s story, the innocent child is “the one” who carries the fire that might give birth to renewed civilization out of near total annihilation.

This is the wonder of this darkest of novels. What distinguishes it as authentic apocalyptic is the one thing that distinguishes biblical apocalyptic—hope. Amid all the destruction, the madness and despair—a despair so deep that the father curses God (“Are you there? Will I see you at last? Have you a neck by which to throttle you? Have you a heart? Damn you eternally have you a soul? Oh God, he whispered. Oh God”)—resides hope. I’ll show you the worst, McCarthy says, of what humans can do to each other. I’ll show you the undoing of civilization, of creation. In the middle of it, I will plant a stem of hope, like “a shoot from the stump of Jesse” (see Isaiah 11), who glows in the waste of destruction “like a tabernacle.”

Father and son keep going down the terrifying road because, despite every evidence to the contrary, the father believes, and so transmits that belief to his son, that somewhere out there are some other “good guys.” And to those people, wherever they are, the father and son “carry the fire.” As long as they hold to those beliefs, they can endure the destruction of everything else. Such hope may be slender, indeed, but it’s all they’ve got. And by the conclusion of this novel, hope may not defeat the evil that howls down the road, but it is enough to hold it at bay.

In McCarthy’s fictional world, evil is real and human depravity devours goodness. The chilling dark of this novel will get inside your bones. A couple of ghastly scenes will turn your stomach. That’s what gives the novel such punch. In the end, the only goodness worth believing in, the only resurrection worth trusting, rises straight from the jaws of the beast. If you’ve heart and stomach for such truth telling, The Road will carry you on a journey that will leave you fearfully hopeful for yourself, but most importantly, for human civilization and for all of creation.

Questions for Consideration.

1) Is McCarthy’s depiction of a post-nuclear world believable? Why or why not?

2) When humans are reduced to survival of the fittest, what, as the novel explores it, is the source of the goodness of the father and son?

3) Do you think the father should have allowed the son to stop and help other survivors along the road, or is their own self-preservation the essential concern of the father?

4) How do the father and son view the nature of God? What are the key passages that show us their views of God?

5) Are you hopeful after reading the novel, or does it leave you discouraged and depressed? Why?

Help explorefaith. Purchase a copy of Cormac McCarthy's THE ROAD at amazon.com.

Copyright © 2009 G. Lee Ramsey, Jr.