| |

Saint

Catherine of Siena Saint

Catherine of Siena

by Judy A. Johnson

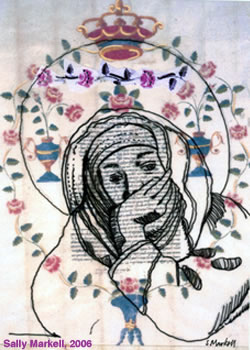

Portrait

of Catherine of Siena by Sally

Markell

I am an introvert. I live with two cats in a one-bedroom apartment. I see it

as place where I can focus and grow spiritually. For me, it is the environment

where I feel closest to God. But life is not that simple. We are called to

model Jesus’s beloved friend Martha—the doer, the people-person,

the one who knew how to take care of others—as well as her sister—the

quiet, listening Mary.

For

people like me, who have struggled all our lives to blend a call

to action with a yearning for contemplation, Saint Catherine

of Siena balances contemplative and active life in a way that inspires both

envy and admiration.

It’s

tempting to divide Catherine’s life

into two distinct periods, the first contemplative and the second active.

The youngest of 24 children, Catherine

began having visions and mystical experiences at age seven. She dedicated

her life to God, vowing perpetual virginity, even cutting off

her hair to make

herself less attractive when she was a marriageable adolescent. She wanted

to become

a Third Order Dominican, a lay position that would still bind her to vows

of poverty, obedience, and celibacy. Although living outside

the convent, Third

Order members could wear the Dominican habit. Her parents opposed this request

for a time; ultimately, her father gave her “a room of her own,” in

which she could remain, fasting and praying. There Jesus came to meet her

daily; among other gifts, he taught her to read.

The

pivotal event in Catherine’s

life came after three years of solitude and ascetic practices. Jesus

stood in the doorway of her room, but instead of

entering as she invited, he told her, “You must come out here now.” She

apparently didn’t question Jesus, but began serving others in Siena,

visiting prisons and nursing plague victims. Eating, which had never been

very important

to her, nearly stopped altogether; according to legend, she lived on the

communion wafer and a bit of water for the last nine years of her life.

Catherine

actively

pursued the work of making peace among the rival families of Italy and

within the Roman Catholic Church, fractured by the pope’s

move to Avignon, France. In 1376, convinced that Pope Gregory

XI, who had been living in Avignon,

needed

to come back to Italy, Catherine and her followers (whom she called her “family”)

walked to France. There she reminded the Pope of a vow he’d made,

but which he’d never revealed. Catherine’s prophetic gifts

stunned and persuaded Gregory; he returned to Italy. Catherine also supported

the

idea of another crusade

and tried to make peace in the face of the Great Schism under Gegory’s

successor, Urban VI.

Although

this neat division of Catherine’s

life into early contemplative and later active segments is tempting,

it’s also misleading. In her early

years, Catherine was a daughter in a busy home, helping with domestic

duties and nursing the sick during outbreaks of the plague. During

her later, more outward

ministry, she sometimes entered a trance in the middle of a conversation.

She also received the stigmata, the marks of Christ’s passion,

on her body, though until her death they were visible only to her.

While

carrying on this active ministry, Catherine wrote or dictated some

400 private letters and one major work, The Dialogue, which has

been

compared to

Dante’s work. This conversation between the soul and God is sprinkled

with spontaneous declarations of love for God and quotations from Scripture

woven

seamlessly into her own speech patterns.

Reading

The Dialogue for a medieval church history class in

seminary, I was immediately attracted to the opening

words,

A

soul rises up, restless with tremendous desire for God’s honor and the salvation

of souls. She has for some time exercised herself in virtue and has become

accustomed to dwelling in the cell

of self-knowledge in order to know better God’s goodness

toward her, since upon knowledge follows love. And loving, she

seeks to pursue truth

and clothe

herself in it.

I

loved that image of the nun’s or monk’s

cell as a place of self-knowledge. I’d

long wondered how Catherine could bear to leave her cozy cell, where

she and Jesus spent a thousand

days together. I’ve

come to realize that the cell of self-knowledge isn’t confined to

a literal place with four walls, as is an enclosed contemplative’s

cell. Catherine could walk beyond her cell’s threshold because

she had learned who she was and what her work was to be. She recognized,

too,

that it was Jesus standing at the lintel; I think

she must have seen Jesus in every face she looked at ever after.

I

too have walked out a bit. Though by attending seminary, I wasn’t

looking for a change in my service or personality, my post-seminary years

have offered

new opportunities for a more unexpectedly active life than I ever would

have predicted: a teaching ministry among the vibrant young people of my

church; opportunities

to companion those in pain; and a book in print at last, with the ministries

that publication can offer.

Catherine

lived out the questions of the Book of Common Prayer’s

baptismal covenant: “Will you seek and serve Christ in all

persons, loving your neighbor as yourself? Will you strive for justice

and peace among all people, and respect the dignity of every human

being?” The expected response is, “I will, with God’s

help.” Catherine offers contemporary seekers a powerful example

of blending contemplation with action.

©2006

Judy A. Johnson |